Cite as Swalwell, K. (2021). Never more urgent. In K. Swalwell & D.Spikes (Eds.) Anti-Oppressive Education in "Elite" Schools: Promising Practices & Cautionary Tales from the Field. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Thank you for picking up One Way to Make Change? Wrestling with Anti-Oppressive Education in Schools of Wealth and Whiteness. The title is a mouthful, I know, and it’s worth explaining how we ended up with it. Originally, we pitched this book as Educating Elites for Social Justice.[1] In an email exchange about the proposal, professor Timothy San Pedro (whose work on culturally disruptive pedagogy (2018) is fantastic) gently nudged me about the term “elite,” wondering if it matched the purpose of the book. In my past work, and in the contributions to this volume, “elite” serves as a synonym for people who seemingly benefit from unjust power relations—those who engage in opportunity hoarding and leveraging whatever privilege they can to ensure that systems built on white supremacy, colonialism, capitalism, ableism, and heteropatriarchy continue to work for them, even as they may espouse nominal support for a more just world.[2] In this framing, an “elite school” connotes an educational institution aiding and abetting in the production of elite status—not a school that is actually better than others, even when we may admire the practices within them.

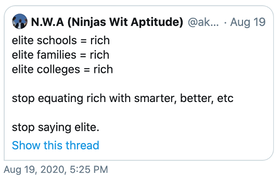

But Dr. San Pedro’s friendly critique coupled with others questioning the use of “elite” led us to reconsider it. For example, check out this Tweet from Dr. Akil Bello, Senior Director of Advocacy and Advancement at FairTest.[3]

Point taken. As someone who taught in a summer program at a swanky boarding school in Connecticut while spending the academic year at a public school in rural Minnesota, I can attest to the fact that a school’s national reputation has very little to do with actual quality (i.e., students’ intellectual curiosity and well-being, teachers’ creativity and competence, etc.) and more to do with its ability to confer social capital via networks of wealth and institutional power. In fact, thinking more about the danger of using “elite”—even with an asterisk explaining our definition—made me suspicious of switching to the term “elitist” as it conveys a belief that one’s elevated status justifies greater power. The “truth” of some higher quality goes unquestioned, reinforcing the powerful myth of meritocracy.[4]

And so, the search was on for a new title. To my co-editor, I half-jokingly suggested How to Help Rich, White Kids Not Become Dangerous Assholes, but something about that seemed unnecessarily cheeky. Ultimately, we landed on One Way to Make Change? Wrestling with Anti-Oppressive Education in Schools of Wealth and Whiteness. The question mark and verb “wrestling” conveyed our growing cynicism with the world given the dumpster fire that is 2020. It’s a frustrating scary mess demanding an urgent reconsideration of what happens in schools of wealth and whiteness—including whether they ought to exist at all.

As we write this, political leaders’ inability and unwillingness to “flatten the curve” of the coronavirus pandemic has led to a devastating economic fallout and hundreds of thousands of deaths, exacerbating existing inequalities like racial disparities in health care, saddling working class parents with impossible childcare dilemmas, and complicating responses to increasingly devastating climate disasters. Unsurprisingly, many well-resourced families and schools are finding ways to avoid the worst of it. For example, some parents are paying thousands of dollars a month for “learning pod” tutors (Berman, 2020) and some private schools are actively recruiting disaffected wealthy parents away from public schools (Blad, 2020) with perks like an epidemiologist on staff and thermal scanners in the hallway (Miller, 2020).

All this is unfolding amidst a uniquely polarizing U.S. Presidential administration and a racial reckoning unseen in decades. In April, people trapped inside by quarantine helped video of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police go viral, sparking worldwide protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Black students launched #BlackAt social media campaigns sharing stories of racial trauma, revealing the superficiality of their prestigious schools’ mission statements and diversity initiatives (Nguyen, 2020). Meanwhile, President Trump called celebrated anti-oppressive curriculum like The 1619 Project “child abuse”[5] and banned federal agencies from anti-bias trainings focused on white privilege or Critical Race Theory.[6]

In response, there has been a flurry of handwringing from “liberal,” white-centered institutions and individuals prompting scholars and activists to caution against performativity rather than actually dismantling longstanding systems of oppression. For example, journalist Erin Logan (2020) quotes historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries about the “distinction between the motivations of white and Black protesters”—the former driven by the “fierce urgency of the future” and the latter responding to “intolerable and immediate injustice.” Says Dr. Jeffries, “What you’re willing to sacrifice, demand and compromise is going to be different. … There is a shared sense of the problem but your immediate objective is fundamentally different.” Dr. Jeffries’ insight has special meaning for anti-oppressive educators teaching in affluent, racially segregated schools. The pacing and objectives of efforts to dismantle the tangled systems of oppression must center the needs and voices of those most immediately and negatively impacted if we have any hope of using young people’s education to redirect their formation as “elites” and to influence the distribution of resources in more just and humane ways. Full stop.

Questions with No Easy Answers

Let’s circle back to the word “elite.” What would actually constitute an elite school in the truest sense of the word as “best,”[7] one that is genuinely anti-oppressive and excels at working towards equity and justice, doing right by the most vulnerable kids and communities through a network of interdependence? What structures, policies, and practices would need to be imagined to bring this kind of education to life—and help it survive in a context of hyper individualism, unsustainable consumerism, and capitalism invested in racism, heterosexism, ableism, and colonialism? Is there any way to leverage “elite” educational spaces for justice?

These are the questions this book seeks to engage, in all their complications and tensions.[8] They have dogged me since I became a social studies teacher nearly twenty years ago and fueled my time in graduate school. For my dissertation, I was lucky enough to spend a year with two accomplished educators engaging in anti-oppressive education (Ayers, Quinn, & Stovall, 2009) at a public and private high school serving predominantly white, wealthy kids. What did social justice education look like in these settings, and which strategies seemed to have the desired impact (Swalwell, 2013, 2015)? It was clear that these students had long ago learned that their voices mattered to people in power and could opine at length on just about any topic. They had years of college preparatory work intellectualizing everything. They had all sorts of external incentives and opportunities to demonstrate their “leadership potential.” It was easy for them to express outrage about oppression long ago or far away, but incredibly difficult for them to examine how it played out in their own families and communities.

Something changed for these students, however, when they had to listen deeply to painful truths from the perspectives of people experiencing oppression rather than articulate their opinions, make emotional rather than purely academic connections, and confront local historical and contemporary injustices rather than distance themselves temporally and geographically from oppression. This project gave me a sliver of hope that anti-oppressive educational efforts in spaces built on wealth and whiteness had a shot at disrupting the cycles of oppression.

To be honest, that sliver of hope comes and goes. Is this “better” teaching and learning still complicit in oppression? Doesn’t it still advantage these kids? In a response to my work, scholars Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández and Adam Howard (2013) rightly urged me not to be too optimistic.[9] They noted that the projection of one’s self as “justice-oriented” has “considerable ideological value” in that it can easily divert attention away from the power of dominant groups by convincing subordinates that they are “compassionate, kind, and giving.” They question “whether and how individuals with economic privilege can ever be effectively involved in social justice efforts and what their role should be.” They continue: "On the one hand, it may be that providing access to the economic resources necessary to support social justice efforts is reason enough to persist in instilling justice-oriented values. ... On the other hand, if providing such resources only serves to reinforce the hierarchical positioning of wealthy elites as morally superior and as capable of enacting the ultimate form of good citizenship by becoming allies with the poor, fundamental social change is highly unlikely." (p.3)

Here’s what really got me: "Unless economically privileged individuals are willing to examine their sense of entitlement and challenge their own privileged ways of knowing and doing, being in solidarity with less fortunate others will remain about improving themselves. At an institutional level, this means that [elite schools] would have to put their very reputations—along with their economic privilege—on the line by becoming not just more diverse ... but by shifting the very fabric of privilege that clothes their elite reputations." (p.4) Their advice has haunted me and inspired me to figure out who else is trying to do this, what is working, and what it even means to “work.”

We don’t know exactly what all of this should look like. Sometimes, it’s easier to see what it obviously isn’t. Take Sadhana Bery’s (2014) example of white teachers at a predominantly white private elementary school facilitating a student play about slavery. Red flags already, right? At a meeting with understandably concerned Black parents, the Head of School explained that the play had come about because some students, all white, had expressed a desire to experience what it was like to have been a slave. Unsurprisingly, "Black parents questioned why the white students’ desires to “experience being a slave” was a sufficient reason for the teachers to produce the play. They asked why the teachers had not consulted them, since their children, the “descendants” of the enslaved represented in the play, would be impacted in ways that white teachers could not know or fully understand. The Head responded that no student was pressured into playing a particular role in the play. The teachers had cast the skit by telling all students, Whites, Blacks, and non-black non-Whites, to choose their roles, saying, “anyone can be anyone” and “if you don’t want to be a slave, you can be a slave master.” (p.339) Education professor Stephanie Jones calls this “curricular violence” (2020) and it is all too common as a form of trauma for kids with minoritized and marginalized identities within majority white, wealthy schools.

We can’t say with certainty that it’s possible for schools founded on cultivating distinction to ever become sites for radical disruptions. Let’s not forget the founding of many “elite” schools is directly related to white, wealthy families resisting desegregation efforts through the creation of “segregation academies” (Carr, 2012), vouchers (Ford, Johnson, & Partelow, 2017), magnet public schools (Buery, 2020), and white flight (e.g., Schneider, 2008).[10] Even some progressive independent schools are tainted with this legacy. For example, the outstanding New York Times’ podcast Nice White Parents reported by Chana Joffe-Wolt documents how white parents wrote letters to New York City school leaders in the 1960s pledging their support for integration but nevertheless sent their children to a majority white private school founded on “progressive values.” Margaret A. Hagerman (2018) explains how progressive, white, wealthy parents still get caught in this “conundrum of privilege.” In her research, Hagerman heard parents express a desire to align their ideals with their parenting choices, but “… when it came to their own children,” found them saying, “‘I care about social justice, but—I don’t want my kid to be a guinea pig.’”[11]

As a well-off white parent who hears the siren calls to hoard opportunity for my own children, that “but” doesn’t surprise me. It does make me nauseous, however, and sharpens my commitment to these questions with no easy answers. Whether we feel sympathy or fury with these families doesn’t negate their existence. And whatever brought them into being, schools of wealth and whiteness are unlikely to disappear any time soon. Yet, within their walls are educators willing to fight the good fight with children who are soaking up all sorts of lessons informing their civic, financial, and social decisions—decisions made more consequential given the institutionalized power many of them are about to literally and figuratively inherit (e.g., Bhalla & Barclay, 2020).

There’s got to be a way to do this, right?

Buckle Up

The following chapters don’t offer easy solutions or trite answers to the wonderings outlined above. Organized into four sections anchored around guiding questions, the contributors offer powerful insights into the problematics of this work and proposals for moving forward. You’ll find everything from philosophy to ethnography to personal narratives to interviews. We have intentionally assembled authors who represent a wide range of identities and backgrounds, encouraging them to leverage their unique perspective, expertise, and experience to address the section’s guiding theme as frankly as possible. I am overwhelmed by their contributions and am so grateful to each of them for their work. My heartfelt appreciation also goes out to my tremendous co-editor and trusted thought partner, Daniel Spikes. While we hold different identities and work in different places—I’m a white teacher educator in Iowa and he’s a Black assistant superintendent in Texas—we both value the dreaming facilitated by the academy as much as the nitty gritty realities of the field. Our hope is that the best of both worlds is represented here.

Part One of this volume (“What’s the Point? Justifying and Framing Anti-Oppressive Education in “Elite” Schools”) wrestles with the ultimate aims of anti-oppressive education in schools of wealth and whiteness. In “Combating the Pathology of Class Privilege: A Critical Education for the Elites,” Quentin Wheeler-Bell explores which model of justice-oriented education for privileged youth is justifiable. Adam Howard outlines the “Intrinsic Aspects of Class Privilege,” using examples from his own teaching to illuminate the development of a “privileged” self-understanding. In “Is Becoming an Oppressor Ever A Privilege? Elite Schools and Social Justice As Mutual Aid,” Nick Tanchuk, Tomas Rocha, and Marc Kruse draw on Indigenous and Black feminist thought to move beyond the discourse of “privilege” towards one of “mutual aid” using excerpts from The Hate U Give to exemplify their theory-in-action.

Part Two (“Red Flags and Mine Fields: Problematic Models of Anti-Oppressive Education in ‘Elite’ Schools”) explores the many ways that equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts at affluent, segregated schools (especially those claiming to be “progressive”) can go very wrong, very fast. In “Beyond Wokeness: How White Educators Can Work Toward Dismantling Whiteness and White Supremacy in Suburban Schools,” Gabriel Rodriguez shares vignettes pointing to ways schools can better serve Latinx students. Petra Lange and Callie Kane use personal narrative in “Dead Ends and Paths Forward: White Teachers Committed to Anti-Racist Teaching in White Spaces” to expose how the binary of “good” and “bad” is unproductive for white teachers working towards antiracism. Ayo Magwood reviews the research on Black and Brown educators’ experiences in independent schools, weaving in candid remembrances to expose the “Unspoken Rules, White Communication Styles, and White Blinders: Why ‘Elite’ Independent Schools Can’t Retain Black and Brown Faculty.” Tania D. Mitchell takes conventional service-learning models to task in “Critical Service-Learning: Moving from Transactional Experiences of Service Towards A Social Justice Praxis.” Kristin Sinclair, Ashley Akerberg, and Brady Wheatley expose the reproduction of privilege at the Island School, a high school study abroad program, in “The ‘Duality of Life’ in ‘Elite’ Sustainability Education: Tensions, Pitfalls, and Possibilities.” Lastly, Cori Jakubiak explores the problematics of English-language voluntourism in “The Possibility of Critical Language Awareness through Volunteer English Teaching Abroad.”

Part Three (“Promising Practices? Ideas for Enacting Anti-Oppressive Education in ‘Elite’ Schools”) taps into the expertise of practitioners attempting to avoid the pitfalls outlined in Part Two. The question mark is intentional as they offer honest assessments of how challenging and uncertain this work can be. In “Living Up to Our Legacy: One School’s Effort to Build Momentum, Capacity, and Commitment to Social Justice,” Christiane M. Connors, Steven Lee, Stacy Smith, and Damian R. Jones provide a step-by-step account of shifting the organizational culture at Edmund Burke School. Robin Moten reflects on the evolution of her social justice class in a predominantly white, wealthy, politically conservative community in “Opening the Proverbial Can O’ Worms: Teaching Social Justice to Educated ‘Elites’ in Suburban Detroit.” In “Facilitating Socially Just Discussions in ‘Elite’ Schools,” Lisa Sibbett analyzes a class discussion enacting and exploring social justice to provide ideas for disrupting the “testimonial quieting and smothering” of students with non-dominant identities. In “Mobilizing Privileged Youth and Teachers for Justice-oriented Work in Science and Education,” Alexa Schindel, Brandon Grossman, and Sara Tolbert explore how the science curriculum can decenter privilege. In “Intersectional Feminist and Political Education with Privileged Girls,” Beth Cooper Benjamin, Amira Proweller, Beth Catlett, Andrea Jacobs, and Sonya Crabtree-Nelson reflect on their facilitation of the Research Training Internship, a program to help Jewish teen girls with racial and class privilege to develop an emerging critical consciousness through youth participatory action research. Lastly, Diane Goodman and Rebecca Drago provide proactive suggestions for practitioners in “‘Not Me!’ Anticipating, Preventing, and Working with Pushback to Social Justice Education.’

In the final section, “Conversations with Colleagues,” edited transcripts of conversations with practitioners complement their personal narratives. Some of these dialogues are available at www.onewaytomakechange.org. Middle school teacher Allen Cross navigates the unresolved tensions and joys of his job in “Out of the Chaos, Beauty Comes: Democratic Schooling in a Progressive Independent Middle School.” Gabby Arca and Nina Sethi contextualize a 3rd grade simulation on wealth inequality and explain their teaching philosophy as women of color in “We’re Afraid They Won’t Feel Bad: Teaching for Social Justice at the Elementary Level.” Alethea Tyner Paradis, founder of Peace Works Travel, shares how she makes sense of opportunities for “Harnessing the Curiosity of Rich People’s Children: International Travel as a Tool of Anti-Oppressive Education.” Former admissions counselor Sherry Smith gives frank advice in “Building a Class: Reflecting on the Role of Admissions and College Counseling in Anti-Oppressive Education.” And in “It Shouldn’t Be That Hard: Student Activists’ Frustrations and Demands,” high schoolers Julia Chen, Haley Hamilton, Vidya Iyer, Alfreda Jarue, Catalina Samaniego, Catreena Wang, and Jenna Woodsmall explain how and why they fight for an anti-racist education in the predominantly white, wealthy suburbs of Des Moines, Iowa.

Is there any way to leverage “elite” educational spaces for justice? The title we landed on[12] leaves open the possibility that our energies may, in fact, be better spent elsewhere. Daniel and I wrestle with this uncertainty, and I’m guessing most readers do, too. More than anything, we hope this book helps support the kind of anti-oppressive education policies and practices that are so desperately needed by so many. Educating young people in spaces designed to protect and reproduce unjust hierarchies may be one way to make change—and, if it is, it’s going to take all of our creativity and savviness to make sure it’s not a co-opted, hollowed out version of what we intended it to be. Our hope as a collective is not to have all the answers, but to start conversations and to spark experiments.

As I tell my three-year old daughter when she’s about to dive into something challenging but exciting: buckle up, buttercup.

REFERENCES

Avashia, N. (2020, September 4). Why landing on the ‘best schools’ list is not something to celebrate. Cognoscenti from WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2020/09/04/boston-magazine-best-high-schools-greater-boston-neema-avashia

Ayers, W., Quinn, T. M., & Stovall, D. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of social justice in education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bellafante, G. (2017, September 22). Can prep schools fight the class war? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/nyregion/trinity-school-letter-to-parents.html

Berman, J. (2020, July 28). From nanny services to ‘private educators,’ wealthy parents are paying up to $100 an hour for ‘teaching pods’ during the pandemic. Market Watch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/affluent-parents-are-setting-up-their-own-schools-as-remote-learning-continues-its-the-failure-of-our-institutions-to-adequately-provide-for-our-students-11595450980

Bery, S. (2014). Multiculturalism, teaching slavery, and white supremacy. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(3), 334-352.

Bhalla, J. & Barclay, E. (2020, October 12). How affluent people can end their mindless overconsumption. VOX. https://www.vox.com/21450911/climate-change-coronavirus-greta-thunberg-flying-degrowth

Blad, E. (2020, August 6). Private schools catch parents’ eye as public school buildings stay shut. EdWeek. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/08/06/private-schools-catch-parents-eye-as-public.html

Bronski, M. (2011). A queer history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Buery, Jr., R.R. (2020). Public school admissions and the myth of meritocracy: How and why screened public school admissions promote segregation. NYUL Rev. Online, 95, 101.

Carr, S. (2012, December 13). In Southern towns, ‘segregation academies’ still going strong. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/12/in-southern-towns-segregation-academies-are-still-going-strong/266207/#:~:text=Quick%20Links-,In%20Southern%20Towns%2C%20'Segregation%20Academies'%20Are%20Still%20Going%20Strong,them%20as%20divided%20as%20ever.

Curl, J. (2012). For all the people: Uncovering the hidden history of cooperation, cooperative movements, and communalism in America. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Dunbar Ortiz, R. (2014). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Ford, C., Johnson, S., & Partelow, L. (2017). The racist origins of private school vouchers. Center for American Progress.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. (2011). Bullshit as resistance: Justifying unearned privilege among students at an elite boarding school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(5), 581-586.

Gaztambide‐Fernández, R., & Angod, L. (2019). Approximating Whiteness: Race, class, and empire in the making of modern elite/White subjects. Educational Theory, 69(6), 719-743.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A., & Howard, A. (2013). Social justice, deferred complicity, and the moral plight of the wealthy. Democracy and Education, 21 (1), 7.

Hagerman, M.A. (2018, September 30). White progressive parents and the conundrum of privilege. L.A. Times. Retrieved at https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-hagerman-white-parents-20180930-story.html

Hannah-Jones, N. (2015). The problem we all live with. This American Life. Retrieved at

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/562/the-problem-we-all-live-with-part-one

Howard, A. (2013). Learning privilege: Lessons of power and identity in affluent schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Howard, A., & Gaztambide-Fernandez, R. A. (Eds.). (2010). Educating elites: Class privilege and educational advantage. R&L Education.

Howard, A. & Kenway, J. (2015). Canvassing conversations: obstinate issues in studies of elites and elite education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(9), 1005-1032.

Howard, A., & Maxwell, C. (2018). From conscientization to imagining redistributive strategies: Social justice collaborations in elite schools. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(4), 526-540.

Immerwahr, D. (2019). How to hide an empire: A short history of the greater United States. New York, NY: Random House.

Jones, S. P. (2020). Ending curriculum violence. Teaching Tolerance, 64, 47-50.

Kendi, I. X. (2017). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. New York, NY: Random House.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New York, NY: One World.

Logan, E.B. (2020, September 4). White people have gentrified Black Lives Matter. It’s a problem. LA Times. Retrieved at https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-09-04/black-lives-matter-white-people-portland-protests-nfl

Miller, C.C. (2020, July 16). In the same towns, private schools are reopening while public schools are not. New York Times. Retrieved at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/upshot/coronavirus-school-reopening-private-public-gap.html

Nielsen, K. E. (2012). A disability history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Nguyen, T. (2020, July 15). Students are using Instagram to reveal racism on campus. VOX.

Retrieved at https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/7/15/21322794/students-instagram-black-at-accounts-campus-racism

Ortiz, P. (2018). An African American and Latinx History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

San Pedro, T. (2018). Abby as ally: An argument for culturally disruptive pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1193-1232.

Swalwell, K. (2013). Educating activist allies: Social justice pedagogy with the suburban and urban elite. New York, NY: Routledge.

Swalwell, K. (2015). Mind the civic empowerment gap: Elite students & critical civic education. Curriculum Inquiry, 45 (5), 491-512.

ENDNOTES

[1] Years ago, Rubén A. Gaztambide Fernández and Adam Howard envisioned a sequel to their edited volume, Educating Elites: Class Privilege and Educational Advantage (2010). My deepest thanks to their mentorship and support for me moving this volume forward.

[2] This description is not exclusive to rich white people, as even those with non-dominant identities can work to secure systems of oppression (Kendi, 2019).

[3] Thanks to my dear friend and colleague Noreen Naseem Rodríguez for sharing this tweet.

[4] Systemic white supremacy interwoven with increasing wealth gaps embedded within heteronormative, ableist, and patriarchal structures continues to produce distinct paths of opportunities and protections for dominant groups. If this is new information to you, the rest of this book will not make sense. Put it down and start reading something else like How to Hide An Empire (Immerwahr, 2019); An African American and Latinx History of the United States (Ortiz, 2018); Stamped from the Beginning (Kendi, 2017); For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America (Curl, 2012), An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (Dunbar Ortiz, 2014), A Queer History of the United States (Bronski, 2011), A Disability History of the United States (Nielsen, 2012), etc.

[5] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-white-house-conference-american-history/

[6] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/M-20-34.pdf

[7] See Neema Avashia’s (2020) essay “Why Landing on the ‘Best Schools’ List Is Not Something to Celebrate” for a thoughtful examination of these questions.

[8] For another take on these questions, see Bellafante’s (2017) article “Can prep schools fight the class war?” which quotes New York City’s Trinity Head of School John Allman’s fascinating letter to families expressing concern that the school produces a “cognitive elite that is self-serving, callous and spiritually barren.”

[9] Both have made invaluable contributions to the small but mighty research base of elite education alongside other wonderful scholars like Leila Angod, Claire Maxwell, and Jane Kenway (e.g., Gaztambide-Fernández, 2011; Gaztambide-Fernández & Angod, 2019; Howard & Gaztambide-Fernández, 2010; Howard, 2013; Howard & Kenway, 2015; Howard & Maxwell, 2018).

[10] For attention to the ways in which rich, white parents currently work the public schools in their favor, see Nikole Hannah-Jones’ fantastic journalism, including the two-part This American Life episode entitled “The Problem We All Live With” (2015).

[11] Thanks to Ayo Magwood for alerting me to this editorial.

[12] Close readers of the book will note that “one way to make change” is a nod to teacher Gabby Arca’s explanation of what motivates her to do this work in Chapter 17.

But Dr. San Pedro’s friendly critique coupled with others questioning the use of “elite” led us to reconsider it. For example, check out this Tweet from Dr. Akil Bello, Senior Director of Advocacy and Advancement at FairTest.[3]

Point taken. As someone who taught in a summer program at a swanky boarding school in Connecticut while spending the academic year at a public school in rural Minnesota, I can attest to the fact that a school’s national reputation has very little to do with actual quality (i.e., students’ intellectual curiosity and well-being, teachers’ creativity and competence, etc.) and more to do with its ability to confer social capital via networks of wealth and institutional power. In fact, thinking more about the danger of using “elite”—even with an asterisk explaining our definition—made me suspicious of switching to the term “elitist” as it conveys a belief that one’s elevated status justifies greater power. The “truth” of some higher quality goes unquestioned, reinforcing the powerful myth of meritocracy.[4]

And so, the search was on for a new title. To my co-editor, I half-jokingly suggested How to Help Rich, White Kids Not Become Dangerous Assholes, but something about that seemed unnecessarily cheeky. Ultimately, we landed on One Way to Make Change? Wrestling with Anti-Oppressive Education in Schools of Wealth and Whiteness. The question mark and verb “wrestling” conveyed our growing cynicism with the world given the dumpster fire that is 2020. It’s a frustrating scary mess demanding an urgent reconsideration of what happens in schools of wealth and whiteness—including whether they ought to exist at all.

As we write this, political leaders’ inability and unwillingness to “flatten the curve” of the coronavirus pandemic has led to a devastating economic fallout and hundreds of thousands of deaths, exacerbating existing inequalities like racial disparities in health care, saddling working class parents with impossible childcare dilemmas, and complicating responses to increasingly devastating climate disasters. Unsurprisingly, many well-resourced families and schools are finding ways to avoid the worst of it. For example, some parents are paying thousands of dollars a month for “learning pod” tutors (Berman, 2020) and some private schools are actively recruiting disaffected wealthy parents away from public schools (Blad, 2020) with perks like an epidemiologist on staff and thermal scanners in the hallway (Miller, 2020).

All this is unfolding amidst a uniquely polarizing U.S. Presidential administration and a racial reckoning unseen in decades. In April, people trapped inside by quarantine helped video of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police go viral, sparking worldwide protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Black students launched #BlackAt social media campaigns sharing stories of racial trauma, revealing the superficiality of their prestigious schools’ mission statements and diversity initiatives (Nguyen, 2020). Meanwhile, President Trump called celebrated anti-oppressive curriculum like The 1619 Project “child abuse”[5] and banned federal agencies from anti-bias trainings focused on white privilege or Critical Race Theory.[6]

In response, there has been a flurry of handwringing from “liberal,” white-centered institutions and individuals prompting scholars and activists to caution against performativity rather than actually dismantling longstanding systems of oppression. For example, journalist Erin Logan (2020) quotes historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries about the “distinction between the motivations of white and Black protesters”—the former driven by the “fierce urgency of the future” and the latter responding to “intolerable and immediate injustice.” Says Dr. Jeffries, “What you’re willing to sacrifice, demand and compromise is going to be different. … There is a shared sense of the problem but your immediate objective is fundamentally different.” Dr. Jeffries’ insight has special meaning for anti-oppressive educators teaching in affluent, racially segregated schools. The pacing and objectives of efforts to dismantle the tangled systems of oppression must center the needs and voices of those most immediately and negatively impacted if we have any hope of using young people’s education to redirect their formation as “elites” and to influence the distribution of resources in more just and humane ways. Full stop.

Questions with No Easy Answers

Let’s circle back to the word “elite.” What would actually constitute an elite school in the truest sense of the word as “best,”[7] one that is genuinely anti-oppressive and excels at working towards equity and justice, doing right by the most vulnerable kids and communities through a network of interdependence? What structures, policies, and practices would need to be imagined to bring this kind of education to life—and help it survive in a context of hyper individualism, unsustainable consumerism, and capitalism invested in racism, heterosexism, ableism, and colonialism? Is there any way to leverage “elite” educational spaces for justice?

These are the questions this book seeks to engage, in all their complications and tensions.[8] They have dogged me since I became a social studies teacher nearly twenty years ago and fueled my time in graduate school. For my dissertation, I was lucky enough to spend a year with two accomplished educators engaging in anti-oppressive education (Ayers, Quinn, & Stovall, 2009) at a public and private high school serving predominantly white, wealthy kids. What did social justice education look like in these settings, and which strategies seemed to have the desired impact (Swalwell, 2013, 2015)? It was clear that these students had long ago learned that their voices mattered to people in power and could opine at length on just about any topic. They had years of college preparatory work intellectualizing everything. They had all sorts of external incentives and opportunities to demonstrate their “leadership potential.” It was easy for them to express outrage about oppression long ago or far away, but incredibly difficult for them to examine how it played out in their own families and communities.

Something changed for these students, however, when they had to listen deeply to painful truths from the perspectives of people experiencing oppression rather than articulate their opinions, make emotional rather than purely academic connections, and confront local historical and contemporary injustices rather than distance themselves temporally and geographically from oppression. This project gave me a sliver of hope that anti-oppressive educational efforts in spaces built on wealth and whiteness had a shot at disrupting the cycles of oppression.

To be honest, that sliver of hope comes and goes. Is this “better” teaching and learning still complicit in oppression? Doesn’t it still advantage these kids? In a response to my work, scholars Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández and Adam Howard (2013) rightly urged me not to be too optimistic.[9] They noted that the projection of one’s self as “justice-oriented” has “considerable ideological value” in that it can easily divert attention away from the power of dominant groups by convincing subordinates that they are “compassionate, kind, and giving.” They question “whether and how individuals with economic privilege can ever be effectively involved in social justice efforts and what their role should be.” They continue: "On the one hand, it may be that providing access to the economic resources necessary to support social justice efforts is reason enough to persist in instilling justice-oriented values. ... On the other hand, if providing such resources only serves to reinforce the hierarchical positioning of wealthy elites as morally superior and as capable of enacting the ultimate form of good citizenship by becoming allies with the poor, fundamental social change is highly unlikely." (p.3)

Here’s what really got me: "Unless economically privileged individuals are willing to examine their sense of entitlement and challenge their own privileged ways of knowing and doing, being in solidarity with less fortunate others will remain about improving themselves. At an institutional level, this means that [elite schools] would have to put their very reputations—along with their economic privilege—on the line by becoming not just more diverse ... but by shifting the very fabric of privilege that clothes their elite reputations." (p.4) Their advice has haunted me and inspired me to figure out who else is trying to do this, what is working, and what it even means to “work.”

We don’t know exactly what all of this should look like. Sometimes, it’s easier to see what it obviously isn’t. Take Sadhana Bery’s (2014) example of white teachers at a predominantly white private elementary school facilitating a student play about slavery. Red flags already, right? At a meeting with understandably concerned Black parents, the Head of School explained that the play had come about because some students, all white, had expressed a desire to experience what it was like to have been a slave. Unsurprisingly, "Black parents questioned why the white students’ desires to “experience being a slave” was a sufficient reason for the teachers to produce the play. They asked why the teachers had not consulted them, since their children, the “descendants” of the enslaved represented in the play, would be impacted in ways that white teachers could not know or fully understand. The Head responded that no student was pressured into playing a particular role in the play. The teachers had cast the skit by telling all students, Whites, Blacks, and non-black non-Whites, to choose their roles, saying, “anyone can be anyone” and “if you don’t want to be a slave, you can be a slave master.” (p.339) Education professor Stephanie Jones calls this “curricular violence” (2020) and it is all too common as a form of trauma for kids with minoritized and marginalized identities within majority white, wealthy schools.

We can’t say with certainty that it’s possible for schools founded on cultivating distinction to ever become sites for radical disruptions. Let’s not forget the founding of many “elite” schools is directly related to white, wealthy families resisting desegregation efforts through the creation of “segregation academies” (Carr, 2012), vouchers (Ford, Johnson, & Partelow, 2017), magnet public schools (Buery, 2020), and white flight (e.g., Schneider, 2008).[10] Even some progressive independent schools are tainted with this legacy. For example, the outstanding New York Times’ podcast Nice White Parents reported by Chana Joffe-Wolt documents how white parents wrote letters to New York City school leaders in the 1960s pledging their support for integration but nevertheless sent their children to a majority white private school founded on “progressive values.” Margaret A. Hagerman (2018) explains how progressive, white, wealthy parents still get caught in this “conundrum of privilege.” In her research, Hagerman heard parents express a desire to align their ideals with their parenting choices, but “… when it came to their own children,” found them saying, “‘I care about social justice, but—I don’t want my kid to be a guinea pig.’”[11]

As a well-off white parent who hears the siren calls to hoard opportunity for my own children, that “but” doesn’t surprise me. It does make me nauseous, however, and sharpens my commitment to these questions with no easy answers. Whether we feel sympathy or fury with these families doesn’t negate their existence. And whatever brought them into being, schools of wealth and whiteness are unlikely to disappear any time soon. Yet, within their walls are educators willing to fight the good fight with children who are soaking up all sorts of lessons informing their civic, financial, and social decisions—decisions made more consequential given the institutionalized power many of them are about to literally and figuratively inherit (e.g., Bhalla & Barclay, 2020).

There’s got to be a way to do this, right?

Buckle Up

The following chapters don’t offer easy solutions or trite answers to the wonderings outlined above. Organized into four sections anchored around guiding questions, the contributors offer powerful insights into the problematics of this work and proposals for moving forward. You’ll find everything from philosophy to ethnography to personal narratives to interviews. We have intentionally assembled authors who represent a wide range of identities and backgrounds, encouraging them to leverage their unique perspective, expertise, and experience to address the section’s guiding theme as frankly as possible. I am overwhelmed by their contributions and am so grateful to each of them for their work. My heartfelt appreciation also goes out to my tremendous co-editor and trusted thought partner, Daniel Spikes. While we hold different identities and work in different places—I’m a white teacher educator in Iowa and he’s a Black assistant superintendent in Texas—we both value the dreaming facilitated by the academy as much as the nitty gritty realities of the field. Our hope is that the best of both worlds is represented here.

Part One of this volume (“What’s the Point? Justifying and Framing Anti-Oppressive Education in “Elite” Schools”) wrestles with the ultimate aims of anti-oppressive education in schools of wealth and whiteness. In “Combating the Pathology of Class Privilege: A Critical Education for the Elites,” Quentin Wheeler-Bell explores which model of justice-oriented education for privileged youth is justifiable. Adam Howard outlines the “Intrinsic Aspects of Class Privilege,” using examples from his own teaching to illuminate the development of a “privileged” self-understanding. In “Is Becoming an Oppressor Ever A Privilege? Elite Schools and Social Justice As Mutual Aid,” Nick Tanchuk, Tomas Rocha, and Marc Kruse draw on Indigenous and Black feminist thought to move beyond the discourse of “privilege” towards one of “mutual aid” using excerpts from The Hate U Give to exemplify their theory-in-action.

Part Two (“Red Flags and Mine Fields: Problematic Models of Anti-Oppressive Education in ‘Elite’ Schools”) explores the many ways that equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts at affluent, segregated schools (especially those claiming to be “progressive”) can go very wrong, very fast. In “Beyond Wokeness: How White Educators Can Work Toward Dismantling Whiteness and White Supremacy in Suburban Schools,” Gabriel Rodriguez shares vignettes pointing to ways schools can better serve Latinx students. Petra Lange and Callie Kane use personal narrative in “Dead Ends and Paths Forward: White Teachers Committed to Anti-Racist Teaching in White Spaces” to expose how the binary of “good” and “bad” is unproductive for white teachers working towards antiracism. Ayo Magwood reviews the research on Black and Brown educators’ experiences in independent schools, weaving in candid remembrances to expose the “Unspoken Rules, White Communication Styles, and White Blinders: Why ‘Elite’ Independent Schools Can’t Retain Black and Brown Faculty.” Tania D. Mitchell takes conventional service-learning models to task in “Critical Service-Learning: Moving from Transactional Experiences of Service Towards A Social Justice Praxis.” Kristin Sinclair, Ashley Akerberg, and Brady Wheatley expose the reproduction of privilege at the Island School, a high school study abroad program, in “The ‘Duality of Life’ in ‘Elite’ Sustainability Education: Tensions, Pitfalls, and Possibilities.” Lastly, Cori Jakubiak explores the problematics of English-language voluntourism in “The Possibility of Critical Language Awareness through Volunteer English Teaching Abroad.”

Part Three (“Promising Practices? Ideas for Enacting Anti-Oppressive Education in ‘Elite’ Schools”) taps into the expertise of practitioners attempting to avoid the pitfalls outlined in Part Two. The question mark is intentional as they offer honest assessments of how challenging and uncertain this work can be. In “Living Up to Our Legacy: One School’s Effort to Build Momentum, Capacity, and Commitment to Social Justice,” Christiane M. Connors, Steven Lee, Stacy Smith, and Damian R. Jones provide a step-by-step account of shifting the organizational culture at Edmund Burke School. Robin Moten reflects on the evolution of her social justice class in a predominantly white, wealthy, politically conservative community in “Opening the Proverbial Can O’ Worms: Teaching Social Justice to Educated ‘Elites’ in Suburban Detroit.” In “Facilitating Socially Just Discussions in ‘Elite’ Schools,” Lisa Sibbett analyzes a class discussion enacting and exploring social justice to provide ideas for disrupting the “testimonial quieting and smothering” of students with non-dominant identities. In “Mobilizing Privileged Youth and Teachers for Justice-oriented Work in Science and Education,” Alexa Schindel, Brandon Grossman, and Sara Tolbert explore how the science curriculum can decenter privilege. In “Intersectional Feminist and Political Education with Privileged Girls,” Beth Cooper Benjamin, Amira Proweller, Beth Catlett, Andrea Jacobs, and Sonya Crabtree-Nelson reflect on their facilitation of the Research Training Internship, a program to help Jewish teen girls with racial and class privilege to develop an emerging critical consciousness through youth participatory action research. Lastly, Diane Goodman and Rebecca Drago provide proactive suggestions for practitioners in “‘Not Me!’ Anticipating, Preventing, and Working with Pushback to Social Justice Education.’

In the final section, “Conversations with Colleagues,” edited transcripts of conversations with practitioners complement their personal narratives. Some of these dialogues are available at www.onewaytomakechange.org. Middle school teacher Allen Cross navigates the unresolved tensions and joys of his job in “Out of the Chaos, Beauty Comes: Democratic Schooling in a Progressive Independent Middle School.” Gabby Arca and Nina Sethi contextualize a 3rd grade simulation on wealth inequality and explain their teaching philosophy as women of color in “We’re Afraid They Won’t Feel Bad: Teaching for Social Justice at the Elementary Level.” Alethea Tyner Paradis, founder of Peace Works Travel, shares how she makes sense of opportunities for “Harnessing the Curiosity of Rich People’s Children: International Travel as a Tool of Anti-Oppressive Education.” Former admissions counselor Sherry Smith gives frank advice in “Building a Class: Reflecting on the Role of Admissions and College Counseling in Anti-Oppressive Education.” And in “It Shouldn’t Be That Hard: Student Activists’ Frustrations and Demands,” high schoolers Julia Chen, Haley Hamilton, Vidya Iyer, Alfreda Jarue, Catalina Samaniego, Catreena Wang, and Jenna Woodsmall explain how and why they fight for an anti-racist education in the predominantly white, wealthy suburbs of Des Moines, Iowa.

Is there any way to leverage “elite” educational spaces for justice? The title we landed on[12] leaves open the possibility that our energies may, in fact, be better spent elsewhere. Daniel and I wrestle with this uncertainty, and I’m guessing most readers do, too. More than anything, we hope this book helps support the kind of anti-oppressive education policies and practices that are so desperately needed by so many. Educating young people in spaces designed to protect and reproduce unjust hierarchies may be one way to make change—and, if it is, it’s going to take all of our creativity and savviness to make sure it’s not a co-opted, hollowed out version of what we intended it to be. Our hope as a collective is not to have all the answers, but to start conversations and to spark experiments.

As I tell my three-year old daughter when she’s about to dive into something challenging but exciting: buckle up, buttercup.

REFERENCES

Avashia, N. (2020, September 4). Why landing on the ‘best schools’ list is not something to celebrate. Cognoscenti from WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2020/09/04/boston-magazine-best-high-schools-greater-boston-neema-avashia

Ayers, W., Quinn, T. M., & Stovall, D. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of social justice in education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bellafante, G. (2017, September 22). Can prep schools fight the class war? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/nyregion/trinity-school-letter-to-parents.html

Berman, J. (2020, July 28). From nanny services to ‘private educators,’ wealthy parents are paying up to $100 an hour for ‘teaching pods’ during the pandemic. Market Watch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/affluent-parents-are-setting-up-their-own-schools-as-remote-learning-continues-its-the-failure-of-our-institutions-to-adequately-provide-for-our-students-11595450980

Bery, S. (2014). Multiculturalism, teaching slavery, and white supremacy. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(3), 334-352.

Bhalla, J. & Barclay, E. (2020, October 12). How affluent people can end their mindless overconsumption. VOX. https://www.vox.com/21450911/climate-change-coronavirus-greta-thunberg-flying-degrowth

Blad, E. (2020, August 6). Private schools catch parents’ eye as public school buildings stay shut. EdWeek. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/08/06/private-schools-catch-parents-eye-as-public.html

Bronski, M. (2011). A queer history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Buery, Jr., R.R. (2020). Public school admissions and the myth of meritocracy: How and why screened public school admissions promote segregation. NYUL Rev. Online, 95, 101.

Carr, S. (2012, December 13). In Southern towns, ‘segregation academies’ still going strong. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/12/in-southern-towns-segregation-academies-are-still-going-strong/266207/#:~:text=Quick%20Links-,In%20Southern%20Towns%2C%20'Segregation%20Academies'%20Are%20Still%20Going%20Strong,them%20as%20divided%20as%20ever.

Curl, J. (2012). For all the people: Uncovering the hidden history of cooperation, cooperative movements, and communalism in America. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Dunbar Ortiz, R. (2014). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Ford, C., Johnson, S., & Partelow, L. (2017). The racist origins of private school vouchers. Center for American Progress.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. (2011). Bullshit as resistance: Justifying unearned privilege among students at an elite boarding school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(5), 581-586.

Gaztambide‐Fernández, R., & Angod, L. (2019). Approximating Whiteness: Race, class, and empire in the making of modern elite/White subjects. Educational Theory, 69(6), 719-743.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A., & Howard, A. (2013). Social justice, deferred complicity, and the moral plight of the wealthy. Democracy and Education, 21 (1), 7.

Hagerman, M.A. (2018, September 30). White progressive parents and the conundrum of privilege. L.A. Times. Retrieved at https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-hagerman-white-parents-20180930-story.html

Hannah-Jones, N. (2015). The problem we all live with. This American Life. Retrieved at

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/562/the-problem-we-all-live-with-part-one

Howard, A. (2013). Learning privilege: Lessons of power and identity in affluent schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Howard, A., & Gaztambide-Fernandez, R. A. (Eds.). (2010). Educating elites: Class privilege and educational advantage. R&L Education.

Howard, A. & Kenway, J. (2015). Canvassing conversations: obstinate issues in studies of elites and elite education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(9), 1005-1032.

Howard, A., & Maxwell, C. (2018). From conscientization to imagining redistributive strategies: Social justice collaborations in elite schools. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(4), 526-540.

Immerwahr, D. (2019). How to hide an empire: A short history of the greater United States. New York, NY: Random House.

Jones, S. P. (2020). Ending curriculum violence. Teaching Tolerance, 64, 47-50.

Kendi, I. X. (2017). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. New York, NY: Random House.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New York, NY: One World.

Logan, E.B. (2020, September 4). White people have gentrified Black Lives Matter. It’s a problem. LA Times. Retrieved at https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-09-04/black-lives-matter-white-people-portland-protests-nfl

Miller, C.C. (2020, July 16). In the same towns, private schools are reopening while public schools are not. New York Times. Retrieved at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/upshot/coronavirus-school-reopening-private-public-gap.html

Nielsen, K. E. (2012). A disability history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Nguyen, T. (2020, July 15). Students are using Instagram to reveal racism on campus. VOX.

Retrieved at https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/7/15/21322794/students-instagram-black-at-accounts-campus-racism

Ortiz, P. (2018). An African American and Latinx History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

San Pedro, T. (2018). Abby as ally: An argument for culturally disruptive pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1193-1232.

Swalwell, K. (2013). Educating activist allies: Social justice pedagogy with the suburban and urban elite. New York, NY: Routledge.

Swalwell, K. (2015). Mind the civic empowerment gap: Elite students & critical civic education. Curriculum Inquiry, 45 (5), 491-512.

ENDNOTES

[1] Years ago, Rubén A. Gaztambide Fernández and Adam Howard envisioned a sequel to their edited volume, Educating Elites: Class Privilege and Educational Advantage (2010). My deepest thanks to their mentorship and support for me moving this volume forward.

[2] This description is not exclusive to rich white people, as even those with non-dominant identities can work to secure systems of oppression (Kendi, 2019).

[3] Thanks to my dear friend and colleague Noreen Naseem Rodríguez for sharing this tweet.

[4] Systemic white supremacy interwoven with increasing wealth gaps embedded within heteronormative, ableist, and patriarchal structures continues to produce distinct paths of opportunities and protections for dominant groups. If this is new information to you, the rest of this book will not make sense. Put it down and start reading something else like How to Hide An Empire (Immerwahr, 2019); An African American and Latinx History of the United States (Ortiz, 2018); Stamped from the Beginning (Kendi, 2017); For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America (Curl, 2012), An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (Dunbar Ortiz, 2014), A Queer History of the United States (Bronski, 2011), A Disability History of the United States (Nielsen, 2012), etc.

[5] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-white-house-conference-american-history/

[6] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/M-20-34.pdf

[7] See Neema Avashia’s (2020) essay “Why Landing on the ‘Best Schools’ List Is Not Something to Celebrate” for a thoughtful examination of these questions.

[8] For another take on these questions, see Bellafante’s (2017) article “Can prep schools fight the class war?” which quotes New York City’s Trinity Head of School John Allman’s fascinating letter to families expressing concern that the school produces a “cognitive elite that is self-serving, callous and spiritually barren.”

[9] Both have made invaluable contributions to the small but mighty research base of elite education alongside other wonderful scholars like Leila Angod, Claire Maxwell, and Jane Kenway (e.g., Gaztambide-Fernández, 2011; Gaztambide-Fernández & Angod, 2019; Howard & Gaztambide-Fernández, 2010; Howard, 2013; Howard & Kenway, 2015; Howard & Maxwell, 2018).

[10] For attention to the ways in which rich, white parents currently work the public schools in their favor, see Nikole Hannah-Jones’ fantastic journalism, including the two-part This American Life episode entitled “The Problem We All Live With” (2015).

[11] Thanks to Ayo Magwood for alerting me to this editorial.

[12] Close readers of the book will note that “one way to make change” is a nod to teacher Gabby Arca’s explanation of what motivates her to do this work in Chapter 17.